I am fifteen years old and sitting halfway up a fairly old white pine tree. I am there with my girlfriend, who has climbed up ahead of me, the tree being in a field adjacent to her parents’ home and therefore one she is quite familiar with. My girlfriend is a much bolder person than I, but I am attempting to conceal this difference and not let on to how nervous I am to be at such a height. The branches are fairly well spread apart, pale grey, and surprisingly full of lichen. The general theme of our conversation, up there in the boughs, is most assuredly something very ambitious: why suffering exists, the reasons to go on living, etc. At some point the concept of happiness comes up, and I make the bold and tragic proposal that perhaps there is something besides happiness that would make life worth living, even to the exclusion of happiness.

This position (or perhaps better, this posturing) ran counter to my fairly mainstream American upbringing, which had taught me that the ultimate purpose in life was probably the satisfaction of my desires (as the child of a second-wave feminist and a draft-dodging art teacher, I was surprisingly malleable to the whims of advertisers). My newly dispassionate view of human happiness was informed in no small way by my burgeoning interest in what I probably called “alternative rock.” As I shifted uncomfortably on that pine branch and tried to sound heroic, I had part of the Belle & Sebastian song “Stay Loose” running through my head:

But my faith is like a bullet

My belief is like a bolt

The only thing that lets me sleep at night

A little carriage of the soul

If it starts a little bleaker

Then the year may yet be gold

Happiness is not for keeping

Happiness is not my goal

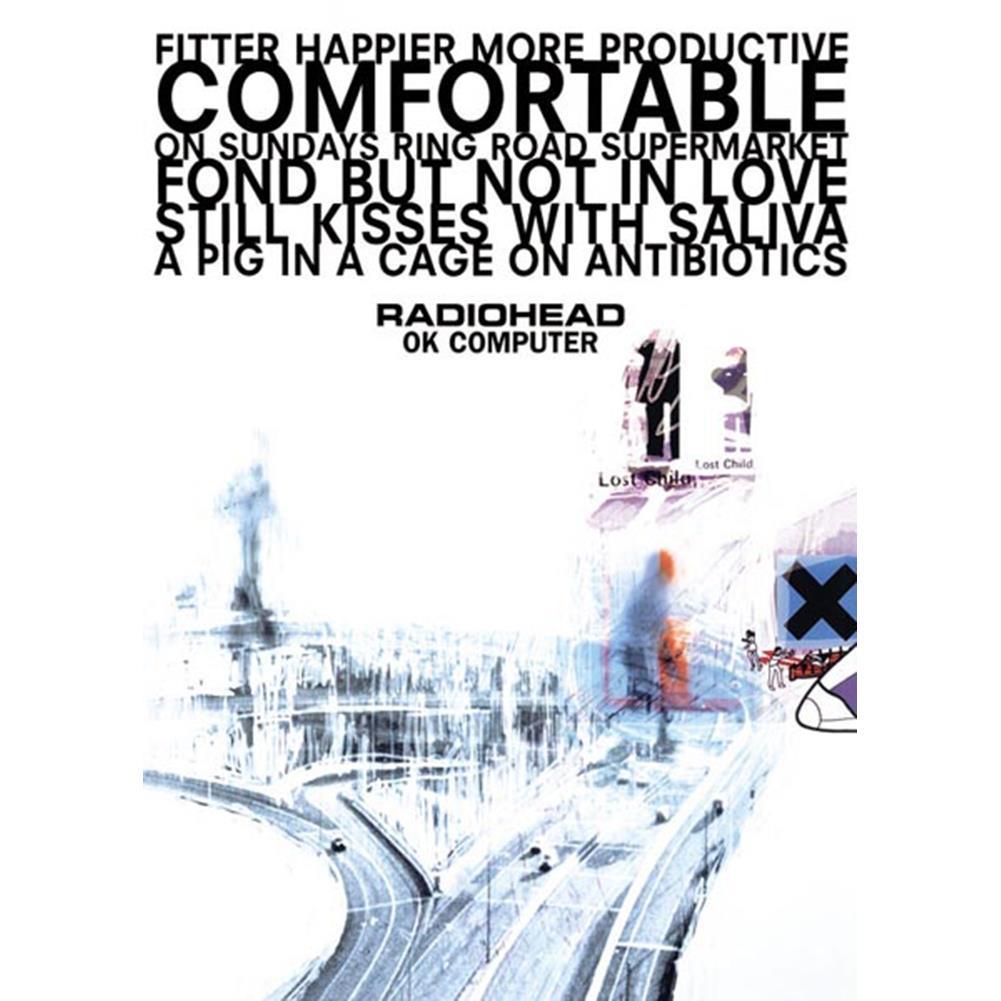

This track from Dear Catastrophe Waitress was among a handful of songs whose lukewarm take on happiness had begun to make an impression on my teenage mind. Another was “Fitter Happier,” the robot-voiced spoken word piece from Radiohead’s OK Computer. Perhaps more important than the song, actually, was the OK Computer poster, which I tacked to the wall of my parents’ basement; it featured a sampling of the disjointed poetry of “Fitter Happier,” which managed to make a fairly thorough imprint on my soul.

Finally, there was Buzzcocks’ “Everybody’s Happy Nowadays,” off of their 1979 “punk masterpiece,” Singles Going Steady. I owned this record because I had one of those older friends who tries to keep you on the narrow path of good taste (probably because it’s so lonely there), and whose recommendations are like divine commands, in that you are free to ignore them, but only at your own peril. I was always a little too sensitive for punk, so I didn’t listen to this album as much The Clash’s Combat Rock, which I purchased around the same time, but the jangly production quality and Peter Shelley’s sneering voice were nevertheless effective transmitters of punkish cynicism: I found myself concurring with the wry disillusionment of “Everybody’s Happy Nowadays” after only a handful of listens.

So, now, as I’ve been reading articles, conducting interviews, and searching for artifacts related to this distinctly (though not exclusively) American pursuit, I have become increasingly aware of my own ingrown bias against the concept of happiness. (It is interesting to note, incidentally, that the three rock bands I listed as influences in this manner are all from the UK.) I’m all for human flourishing, mental health, “well-being,” and so forth, but I find that I approach “happiness” with a rather durable brand of cynicism. And while I originally imagined that my challenge, as an amateur cultural researcher, was to determine the meaning of “true happiness” (as differentiated from what marketers use to sell soda and washing machines, and what songs like “Fitter Happier” do such a neat job of lampooning), I have begun to be more and more comfortable with leaving my acquired definition of happiness where it is. I have been putting effort into deepening the concept so that it better fits my personality, disposition, and philosophical perspective, but perhaps the problem is not that the meaning of happiness has been corrupted, but that it was never sufficiently meaningful in the first place. In other words, maybe the challenge is not to give substance to the pursuit that, perhaps more than anything else, is representative of the American project, but to begin to imagine other goals that are better suited to the human project.